| The Journal of Provincial Thought |

I was a bookish kid, often laid up with childhood illnesses, reading in bed, trudging back and forth to the town library, sent to read in the grade school library when I got too far ahead in lessons. People assumed I was snooty and “literary,” when I was only a reading addict, a confirmed, hopeless bibliomaniac. And while I read “real” books, I also devoured comic books and comic strips.

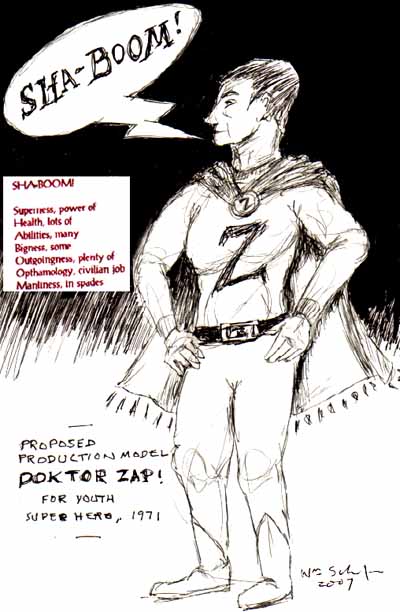

It was—without my knowledge or consent—the Golden Age of comic books and the zenith of newspaper strips. I witnessed the titanic life-and-death-struggle of Superman v. Captain Marvel. I preferred Marvel, because of his mythic background, while the temper of the time went with Supe, from a science fiction genesis—born on Krypton, sent via rocket ship to earth, given his powers by science and genetics. I liked how Capt. Marvel simply said “Shazam!” (an acronym drawn from gods’ and goddesses’ names) and became Billy Batson, lame newsboy. Why bother with rational explanations? I read strange comics like Blackhawk, because it involved a squadron of freebooting multinational fliers using the dodo-like Grumman Skyrocket twin-engined fighter (the only success the plane ever achieved) and because their leader uttered the warcry “Hawkaaaaaa!” whenever they engaged sneaky, slant-eyed, buck-toothed, treacherous N*ps, who always went down in flames and tears, eyes goggling behind thick spectacles.

I liked the way Cap battled grotesque supervillains like Dr. Sivana, a skinny, four-eyed guy (my chemistry teacher in high school), who taunted Cap as a “big red cheese” and Mr. Mind, a tiny genius caterpillar who directed his wicked, worm-enabling gang of human thugs via a loudspeaker hung around his first segment. I read Plastic Man because it was weird art, with ole Plas blending his infinitely elastic body into the environment as a table radio or a wall mural or a sofa, always banded in lurid red, blue and yellow, as he was. I also liked his dumbbell sidekick Woozy Winks, a useful slob.

My regular buys (my father and I walked to Owen’s Drug Store every Friday night, when he bought Life, Colliers, SatEvePost and Black Mask detective pulps, while I loaded up on comic books) were Daredevil (not the later Stan Lee travesty), Crime Does Not Pay, Batman, Wonder Woman (guiltily—it might be girlie) and later the cornucopia of brilliant EC comics—Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, Weird SF, Mad and its offspring. I liked Daredevil because the superhero was assisted by incompetent juvenile delinquents, The Little Wise Guys, especially the big goof Scarecrow, with a haircut like a robin’s nest. Crime Does Not Pay was creepy because it made crime exciting, was supposed to be based on true stories and was overseen by Mr. Crime, a slavering ghoul. (The “Does Not Pay” part of the title was negligently fotched onto a prominent CRIME banner, and everybody called it Crime comics.)

Batman was sinister in a goofy way, and the bizarre villains recalled the newspaper strip Dick Tracy, which also fascinated me because its creator Chester Gould was mad as a hatter, chained gibbering in an attic to pen his panels. How else account for such weirdly mutated characters as Pruneface, No Face, Flat Top and Gravel Gerty and for the visible bullets that spiraled through bad guys whenever hatchet-faced

The Batman villains were more comic than psychotic, but the Penguin and the Joker were weird enough. Batman and Robin were a study, too, not high on the mental health charts. I read Wonder Woman because she was sexily drawn in her short shorts and bulletproof bra, and because I liked her transparent car and plane and her little magical lasso. It was fey in a healthily feminine way, to my mind. If women could be tough, they needed star-spangled tights, golden boots, lusty thighs and unruffled coif and makeup.

My comix tastes were erratic and irrational. I read some strips because of the high esthetics in the art work—Prince Valiant was finicky and effeminate in its stories (guys in pageboy bobs!—we knew what that meant!), but the drawing was loaded with astounding, obsessive detail. I didn’t read it so much as ogle it, absorb it like a Daumier lithograph or Rembrandt etching. Alley Oop I could never follow, but I loved the stylized deco-like drawing, especially the dinosaurs. I read Smilin’ Jack for the planes in the background and little signs posted throughout for air shows (“Hades Copters Fly in the Ointment,” Mad parodied them). Smokey Stover fell into the same category, a brilliant, utterly unpredictable frieze of surrealism, peppered with nonsensical doubletalk (Notary Sojac! Foo!), but which seemed funny in a nutty way—like Three Stooges shorts or Ernie Kovacs’ TV routines.

I loved the tough-guy war comic books that erupted during the Korean War. They were drawn with hypnotic and obsessive realism, down to the last machine-gun belt loop and hand grenade segment, and sound effects were rendered in pure onomatopoeia (lettered luridly as large as the action itself to indicate eardrum-popping Armaggedon)—takatakatakataka or buddabuddabudda or krump! or kapow! Soldiers were blown up, mowed down, mutilated, annihilated with gusto. War was hell, but it looked good from panel to panel.

I loved EC’s Weird SF, retelling classic science fiction tales in a few dozen panels (with brilliant editing) and recycling the alien-language phrase spa fon as a name, an epithet or a question. The gorgeously detailed drawings were by Will Elder, Jack Davis, Wallace Wood, Harvey Kurtzman—the most fascinating and skilled cartoon draftsmen ever sheltered under one roof, as clinically disturbed as Chester Gould but a lot funnier.

I loved the eccentricity and cuteness of Walt Kelly’s Pogo, simultaneously a loveable-animal fable and a fairly sharp parody of such. It advanced views on race, politics and social mores in post-War

On the other hand, I despised, ignored or abominated comic books and strips now canonized as classics: wimpy comics like Little Lulu or Nancy, overwhelmingly girlie in word, thought, deed and image, meandering oddball things like Henry (a bald, mute kid whose feet were malformed?), The Little King (who cared about mute royal midgets?), Casper the Friendly Ghost (give me a break!—ghosts are horrible, scary and loathsome), Little Orphan Annie (I hoped Punjab would decapitate her, Daddy Warbucks and Sandy, the whole blank-eyed crew, with one mighty scimitar-stroke), L’il Abner and Snuffy Smith (caricature hillbillies off to limbo, except for Daisy Mae and her fetching bikini-sized outfit!), Superman and his endless tribe (although I loyally adored Capt. Marvel Jr., Mary Marvel, Grandpa Marvel and that sequel ilk) and most talking-animal comics, though I tolerated the brilliant Carl-Barks-conceived Donald Duck comics, which far excelled the animated originals.

I regarded teen-age-targeted comics dubiously—Archie, Harold Teen and the gang at the Malt Shoppe seemed archaic and bordering on flatulent romance (Betty and Veronica might have bolted from a tedious working-girl strip). They weren’t like any teenagers I knew, and I had only faint sympathies for working-class Archie and Jughead vs. richboy Reggie. They all seemed sissy. Other quasi-soap operas like Mary Worth or Mark Trail reeked of fustian sentimentality.

I read irregularly complex adventure stories like Terry and the Pirates, Scorchy Smith,

My world of cartoons included adult features, editorials and one-panel works—Our Boarding House, Out Our Way, the superb wartime work of Bill Mauldin (I still believe Willie and Joe to be real, historical characters), the mordant political cartoons prompted by the Cold War, with their vast nuclear bombs, mushroom clouds, apocalyptic imagery. When I ran across great cartoons from back beyond my event horizon—Krazy Kat, Little Nemo in Slumberland, the one-panel masterworks of Rube Goldberg—I was bowled over by their freedom, elegance and evocation of the whole cartoon universe. I can’t tack them into my context, but they seem forecasts of my cartoon life. Bits of ur-language and phrases from cartoons I absorbed, since comics are

Comics freeze time and stop motion, panelize reality into little units of drama and emotion and thought. They create a graphic shorthand of brilliant caricature and character-typing that compress complex stories and ideas into tiny spaces. It was a visual world that could be manipulated by me—movies whizzed by at 24 frames per second in a linear way, like impoverished reality, but a comic book was the same kind of time machine as a book—you could page back, re-read, review as you went along, even jump ahead and spoil the ending.

The visuals were gorgeous—screamingly vivid in 3-color pulp printing, boldly penned in by black bars and balloons, elastic and arbitrary. Comic artists set up and shattered conventions in every issue, leaping outside the bar lines, switching from color to black and white, distorting time and space as glibly as any surrealist painter, dispensing with language or giving us dramatic dialogue, stream of consciousness and free-form dreams more freely than James Joyce.

And—the most miraculous idea that lingers—it was all for a dime! In the corner of each cover a little circle enclosing 10¢! A kid-sized treat scaled for a kid-sized universe. I tried to envision grown-ups who wrote and drew the comix, and my imagination always failed. I saw in my mind kids who had grown bigger, adults frozen into perpetual youth. Even then, that seemed a wonderful, accessible possibility. ###

![]()

| jptArchive Issue 6 |

![]()

| Copyright 2008- WJ Schafer & WC Smith - All Rights Reserved |

COMIX